A large sunspot has been the reason for several major eruptions in this date. Charged particles from the events have been hammering orbital spacecrafts. The storms caused minor glitches on the Sun-watching SOHO spacecraft and forced scientists to put two of its instruments into “safe mode,” not unlike an electronic nap. The sunspot group is “one of the most flaring regions of the last few years,” said Bernhard Fleck, SOHO Project Scientist with the European Space Agency (ESA).

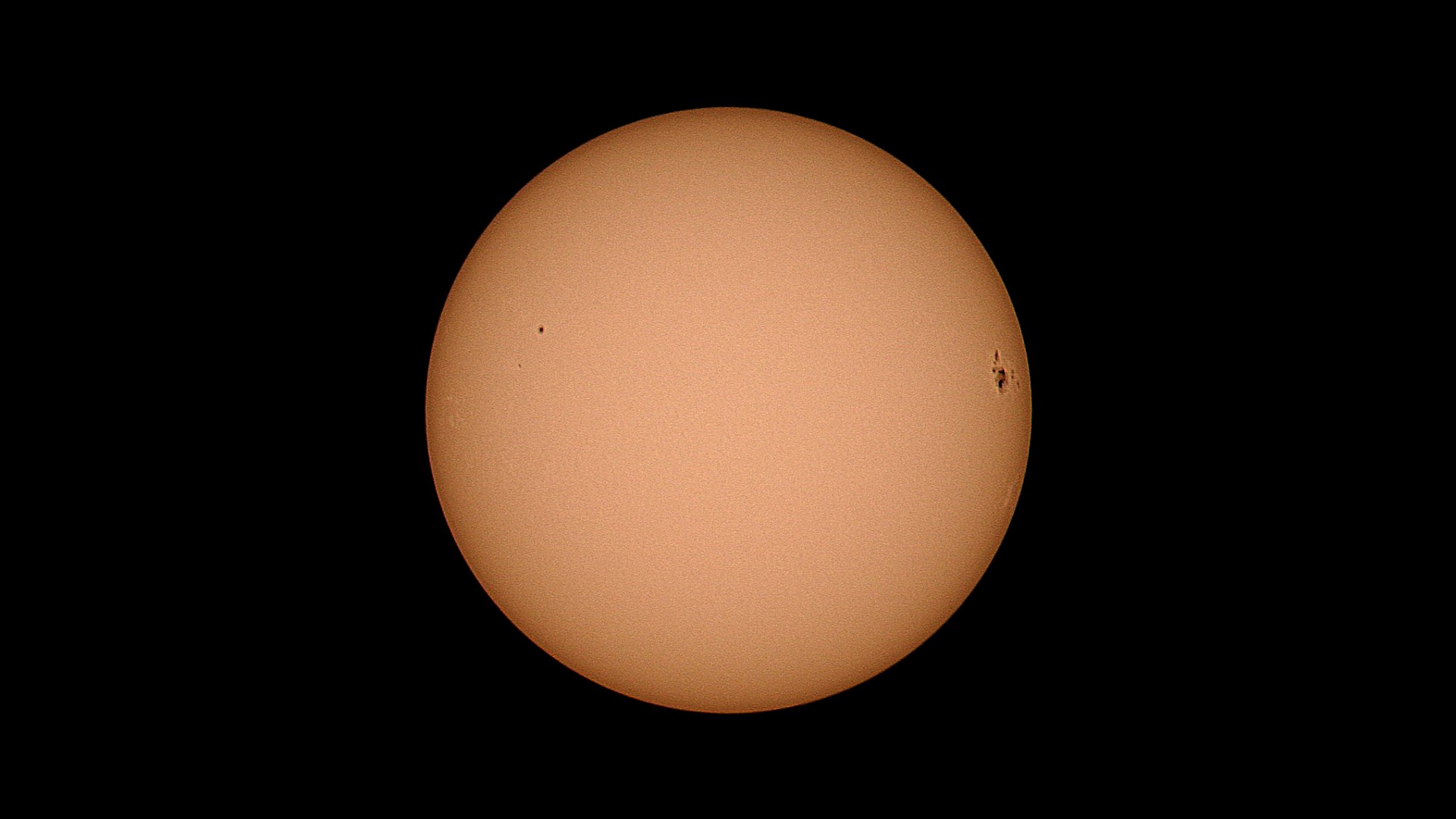

Sunspots are regions of intense magnetic energy, cooler than the surrounding solar surface. They’re a bit like corks in a shaken bottle of champagne, and when they cut loose, radiation and matter are flung into space. Flares of visible light and X-rays are rated M for medium and X for strong, with an accompanying number that signifies further intensity. The sunspot group, numbered 720, has delivered 15 M-class flares and five X-class flares. At around 2 a.m. ET Thursday, it unleashed an X7, one of the most intense measured in recent years.

SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory) is run by ESA and NASA. It and the geostationary satellites orbit much higher than many other satellite and are more directly exposed to storms.

The Sun is divided into three main layers: a core, a radiative zone, and a convective zone. The Sun’s energy comes from thermonuclear reactions (mostly converting hydrogen to helium) in the core, where the temperature can reach 28 million degrees Fahrenheit. The energy radiates through the middle layer, then bubbles and boils to the surface in a process called convection. Charged particles, called the solar wind, stream out at a million miles an hour.

Scientists estimate that it takes a few hundred thousand years for photons, the basic units of light, to escape the Sun’s core and reach the surface. They arrive at Earth about 8-and-a-half minutes later. If you stood on the Sun, its gravity would make you feel 38 times more heavy than you do on Earth. Don’t recommend trying it.